Turonne Hunt

Amy Rasor

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech)

Margaret Becker

Patterson, Ph.D. Research Allies for Lifelong Learning

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the role of leadership training in developing voice in adult learners. Twenty-one (21) adult education programs were randomly selected for evaluation: 13 programs received an 8-hour leadership training and 12 subsequently completed a leadership project; the remaining eight served as control programs. Qualitative methods were used to analyze observational notes and videos for each program on two separate occasions, both pre- and post-leadership training. Four overarching themes were identified as essential in cultivating adult learner voice and leadership: community and collaboration, laughter and comfort, selfmotivation and perseverance, and opportunity. Our findings on how adult learners in leadership roles, in contrast with learners in control settings, interacted with instructional and administrative staff and peers offer insights into and examples of learner development of voice. Finally, we present implications for staff and programs to enhance practice. Our recommendations include building relationships, fostering community and collaboration, and encouraging voice through activities.

INTRODUCTION

In a recent experimental evaluation of leadership, adult learner voice played a key role in learners’ growth as leaders. After training in leadership from VALUEUSA, adult learners and staff in 12 programs developed and conducted a leadership project in community or staff awareness, communications, or fundraising to benefit the program or purchase needed materials (Patterson, 2017).

VALUEUSA envisioned that adult learners would gain knowledge and skills through leadership activities. During projects, adult learner leaders learned to share opinions and ideas. “You need to [speak] up and say what’s on your mind,” wrote a learner. Finding voice was part of actively engaging in outreach or fundraising. “I stood and told the rest of the students about what we were doing,” wrote another learner. “I learned how to communicate with others” (Patterson, 2016a, pp. 3-4).

How can staff help adult learners find and share their voices through leadership? Our findings on how adult learners in leadership roles, in contrast with learners in control settings, interacted with instructional and administrative staff provide insights into and examples of learner development of voice, as well as implications for staff and programs to enhance practice.

LITERATURE REVIEW

What do we mean by “adult learner voice”? An early notion of “voice” is ability “to express ideas and opinions with the confidence they will be heard and taken into account” (Stein, 1997, p. 7). Sperling and Appleman (2011) present voice as a metaphor for agency and identity, contending that voice may be both individually realized and socially constructed, lost and found, and influenced by others.

Settings Encouraging Voice

Finding voice is rooted in gaining self-confidence, understanding others’ ideas, and taking responsibility. A fundamental “benefit from learning of every kind is a growth in self-confidence” (Schuller, Brasset-Grundy, Green, Hammond, & Preston, 2002, p. 14). Schuller et. al. (2002) found that increases in self-confidence enabled adult learners to advance opinions, engage in reflective practices, and develop identity. Learners overall experienced greater tolerance for conflicting viewpoints and could adopt new responsibilities within their communities.

Adult learner voice flourishes in settings of collaboration and trust. Mezirow advocates for collaborative discourse and a trusting, inclusive, caring environment, including “equal opportunity to participate in discussion, to have their voices heard and understood” (2007, p. 15). A sense of belonging to a learning community tends to increase engagement and continued attendance (Schwarzer, 2009) and supports learner comfort in approaching peers and staff with previously unexpressed concerns (Shiffman, 2018).

Opportunity to raise questions helps optimize learner voice. Schwarzer (2009) suggests that encouraging adult learners to develop and articulate their own questions increases ownership of learning. Opportunities for asking questions are essential, especially when learners are hesitant (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2017).

Voice and Learner Involvement

Involving adult learners in curriculum design, including assessing and working toward enrolling learners’ goals, fosters confidence that voices are heard and valued (Florez & Terrill, 2003; Schwarzer, 2009; Shiffman, 2018). Further, learners with a significant role in curricular design are better equipped to advocate for themselves outside education (Toso, Prins, Drayton, Gnanadass, & Gungor, 2009). Despite its documented benefits, programs adopting learner involvement are the exception, not the norm. According to Toso et. al. (2009, p. 151), “few adult education programs are of and by learners, meaning that students have few opportunities to make substantive decisions” about learning or program emphases.

Adult learners may feel timid about speaking for numerous reasons, including perceived power differentials between educators and learners (Shiffman, 2018) and even among peers (Sperling & Appleman, 2011). Ramirez-Esparza et. al. (2012) found that adult English learners with little formal education ask for help or initiate group activities less often and exhibit introverted behaviors more often than peers with more education.

Participation in adult education may encourage finding voice. For English learners, a change in viewpoint, as well as greater self-esteem and empowerment, may result from participation (King, 2000). Another study found that advanced English learners became comfortable advocating for their children, while beginning learners hesitated to exercise behavior they perceived as causing trouble (Shiffman, 2018).

Voice and Learner Leadership

For learners, making their voice heard is critical to advancing their narrative or seeking social change. One avenue for sharing such narratives is Adult Learners’ Weeks, festivals which serve to encourage involvement in adult literacy and make successes visible to legislators (Tuckett, 2018). Hearing learner stories and viewing learners as assets to communities strengthens advocacy for them in other arenas (Kennedy, 2019).

Archie Willard, founder of VALUEUSA, argued that “learners, to become leaders, need uninterrupted opportunities to tell their life story” (NASEM, 2017, p. 37). Adult learner leadership is described as “adult learner involvement in all components of the [adult education] program and every phase of its organization and function” (Patterson, 2016a, p. 3). Furthermore, “participation in leadership activities—especially being validated by others, putting forth ideas, and having others listen to them—can enhance students’ self-esteem and sense of worth” (Toso et al., 2009, p. 157).

Higher levels of engagement can lead to gains in agency, leadership proficiencies, and connections with both peers and educators (Mitra, 2004). In a study of long-term leadership roles on a student advisory council, the council provided student leaders opportunities to advocate for themselves and utilize skills they learned in the program in outside settings. Both student leaders and staff indicated council participation enabled students’ voices to be heard (Drayton & Prins, 2008).

Voice in adult learner leaders is also needed for shared program planning and governance. Parental Advisory Council members for a family literacy program used voice to help plan curricula for adults and children, choosing topics that aligned with their own needs (Toso et al., 2009). Even where a power differential between staff and students is assumed, a co-governance model can emerge if learners are given leadership roles (Freiwirth & Letona, 2006).

After completing our review of literature, we determined two research questions for this paper. Both questions reflect the qualitative experiences of learner voice through leadership and the role that others played in fostering gains in voice

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

METHODS

Our analysis for this paper occurred with data from a larger two-year, mixed methods leadership evaluation employing random assignment of programs. Its purpose was to evaluate how adult learners benefitted a program as they pursued their own learning and leadership goals. In 2014-15 (Year 1), 21 programs in multiple U.S. states were selected at random as either participating or control programs, and baseline data were collected from all 21 programs. Thirteen participating programs received VALUEUSA leadership training and 12 developed a learner-led project; eight control programs continued to run their programs as usual. Adult learners took surveys on educational experiences and perceptions of leadership, followed by critical thinking and writing assessments. Their interactions with staff were also observed onsite. Data collection continued in 2015-16 (Year 2), to follow up on changes that occurred (Patterson, 2016b).

Participating adult learners attended a two-step eight-hour training that focused on understanding and applying the components of leadership. Step 1 provided learners with foundational knowledge of critical thinking, how organizations are structured, and how to prioritize. Also, adults learned to identify internal and external assets and how to collaborate. During Step 2, learners and staff completed a needs assessment to recognize needs specific to their program. The leadership project topic was chosen from the needs assessment, and the learners and the staff began discussing next steps (Patterson, 2017)

Next, adult learners and staff developed and conducted a leadership project. Twelve groups implemented leadership projects representing one of three types: awareness, communications, or fundraising. Raising awareness was the goal of five leadership projects, which focused on outreach to potential adults and tutors, awareness of adult education in local neighborhoods, or staff awareness of learners. Communications, either in the program or in the community, was the focus of two leadership projects. Five fundraising projects typically sought to raise funds to benefit the program or purchase needed materials (Patterson, 2017).

Observation and video recording permitted evaluators to measure dynamics occurring when staff and learners interacted and whether learners might speak out more after participating in leadership. An observation protocol was developed to ensure inter-observer consistency. Positions of staff, adult learners, and researchers in the room were noted, and the setting was carefully described.

Every 5-10 minutes an observer noted whether interactions were staff or learner led, following an approach described by Mellard and Scanlon (2006). In both years, staff tended to lead interactions frequently, across conditions, yet participating adult learners led interactions significantly more after leadership activities than did staff. Control learners actually spoke up even less in Year 2 than in Year 1, with staff dominating interactions (Patterson, 2017).

In settings where all adult learners gave informed consent to video-recording, interactive sessions were recorded. To provide auxiliary information on how often staff and learners spoke in sessions, we examined videos, observation notes, or both. In most settings, adult learners and staff seemed comfortable and appeared to feel safe, physically and emotionally.

Our qualitative analyses employed phenomenology, an approach used by researchers to study people’s conscious experience of their lifeworld, that is their “everyday life and social action” (Merriam, 2009, p. 24-25). We reviewed 43 observation protocols, eight sets of videos, and a brief movie that consisted of Year 1 and Year 2 data. Dedoose (version 8) software was utilized for qualitative analyses. As data were reviewed, essential concepts and ideas were noted by each researcher. We discussed and synthesized our individual findings and reflections to produce four themes connecting voice and leadership.

FINDINGS

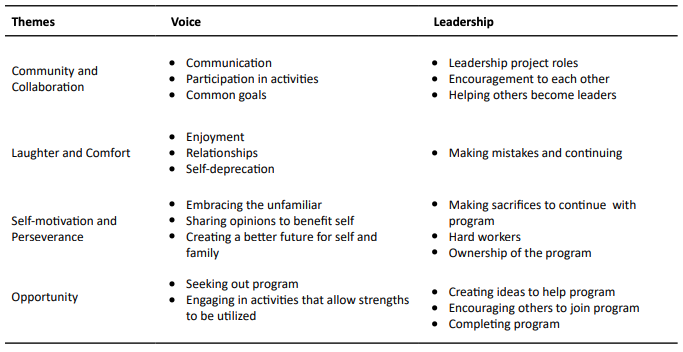

Reviewing data qualitatively as described in the methods allowed us to identify four overarching themes connected to learner voice and leadership, as displayed in Table 1: Community and Collaboration, Laughter and Comfort, Self-motivation and Perseverance, and Opportunity. These themes are embedded and cultivated in participating programs that promoted learner voice and created space for adult learners to become leaders. These themes were notably less visible in control programs. We present major findings and highlight examples of participants’ voices.

Community and Collaboration

Adult learners in this evaluation thrived when a sense of community and collaboration existed within the learning space. Peter Block offers a multi-layered definition of community:

Community… is about the experience of belonging…. The word belong has two meanings. First and foremost, to belong is to be related to and a part of something.… The second meaning of the word belong has to do with being an owner…. What I consider mine I will build and nurture. The work, then, is to seek in our communities a wider and deeper sense of emotional ownership. (Block, 2008, p. xii, emphasis in original)

A learner in a participating center said, “Everybody wants to feel a part of something. Before I came to class, I didn’t have that, I made newer connections. It was a refreshing feeling.” “[D]on’t let others feel less important” was a takeaway for another learner. One learner succinctly stated, “I learned that I have a voice in my community.”

According to Cherrstrom, Zarestky, and Deer (2018), adult learners build community for support and learning. Based on our observations, learner leaders appeared more apt to participate and try to complete tasks. Classmates would readily help each other and encourage each other to keep trying. One participant did so by “helping and agreeing with what we had in front of us to do. Making the project even easier to go forth.” Another participant added, “And helping each person in any need they needed for our GED learning I person[al]ly help everybody. By having project we invited everyone. I spoken on every class and to let them know how important we all are to each other. We are the voice to speak up.” One learner in a participating center seamlessly led a discussion, prompting other learners for input, while translating from Spanish to English and vice versa so that learners with limited English skills could still be an integral part of the conversation. Learner leaders helped other learners to become leaders by encouraging them to lead and being supportive during the process.

In addition to peer-to-peer interactions, staff cultivating adult learner voice is important. In our observations, staff asking for volunteers to answer a question often resulted in silence, but calling on students by name almost always encouraged them to speak. Simple words of affirmation from staff such as “Very good!” led to increased learner participation during problem-solving activities. Conversely, continued negative staff feedback observed in two settings disengaged many learners. Some of the most poignant cases of staff encouraging learner voice occurred in participating centers when learners and staff were seated together in a circle, with staff providing only minimal prompts and listening to learners.

Collaboration can be defined as working with someone to produce or create something (Patterson, 2016b). Leadership projects required adult learners to collaborate to complete goals, and collaboration added to the group’s sense of community. Learners indicated reaching collaborative goals when they shared ideas, led a lesson or meeting, or became a project leader. Participants had to use learner voice to collaborate on projects and, while doing so, leadership qualities were being cultivated. One learner wrote, “I learned how important compromising can be.” Another wrote, “I learned about the importance to work in a group to decide how to resolve any problem.”

Laughter and Comfort

Laughter was a recurring theme, present in almost all observations. A key difference between participating and control centers was the way humor was used. In control centers, humor mainly served to diffuse a tense atmosphere. Staff sometimes related a humorous anecdote as a session started, and one even joked about her age, to engage adult learners and encourage them to relax. In one control center, learners whispered and laughed amongst themselves nervously in response to their teacher’s brusque demeanor in presenting the English as a Second Language lesson.

Laughter was also present in leadership settings. Teachers and learners had reached a level of comfort that allowed them to enjoy themselves and laugh with each other at common mistakes. Key to optimizing learner potential as a leader is staff understanding that an adult learner needs to be able to laugh with peers and staff. Laughter is the universal language of joy and learners appeared to need that at times to deal with the hardships of learning a new language and skill set. Everyone could understand laughter without difficulty.

At times, we noticed that laughter was self-deprecating in both conditions, especially when the learner made a mistake that was made repeatedly, and the teacher would join in the laughing. A learner laughing at him/herself showed a level of comfort with the whole group, without negative impact. Learners assisted that person and they continued with the activity. “I learned new social interaction skills,” emphasized one adult learner.

Self-Motivation and Perseverance

Self-motivation and perseverance are essential traits an adult learner needs to complete the program. A tremendous number of environmental factors can hinder learners from starting, finishing, or reaching full potential in adult education programs. Jobs, family situations, and money are a few hardships facing adult learners (Patterson & Song, 2018). Learners appeared to want a better life for themselves and their families. A 16-year-old working toward a high school equivalency credential indicated she is usually shy and awkward but recognized a need to step out of her comfort zone: “That’s where my leadership is going to get me a job. To be a [crime scene investigator] I need to take a lot of science and will need to step up and lead.”

Children were present in many sessions we observed where childcare was lacking; despite their presence, most parents managed to keep focused on learning. Having to juggle learning and responsibility for children creates a hardship, but it appeared worth it to these participants. Being able to speak with their child’s teacher, for example, was tremendously important for parents. One adult learner wrote, “At first I not know English. At my son’s school there I held back because I not understand what the teacher say about my son.” Another spoke of the difference the program made for her: “I can now speak with the people and I feel more comfortable. I used to feel afraid. I can read for my son and speak with his teacher frequently.” Other students relayed that the program helped them learn how to buy medicine and to make healthy choices.

Adult learners are generally hard workers. Most learners worked full-time jobs or stayed at home with multiple children; still, these learners were active in the program and took on roles that benefitted them and the program. One participant joined the student council, did presentations, and tutored peers to help them reach success; she noted, “I practiced to speak up in front of a large group of people. Such as conference and workshop. Trying to help others and teaching/guiding other people usual[l]y helps you learn or reinforce what you are trying to teach or transmit. So I learnt how far you can go when you are committed to reach your goals. I won the ‘Adult Learner of the Year Award’ from [state] and I also won [a] scholarship to become a CNA”.

The theme of perseverance surfaced repeatedly in participating centers. One learner, speaking about continuing to learn English after eight years in the USA, encouraged others: “Don’t surrender! Try and try and try!” Another added, “If we have one object, one goal … one day we’re gonna reach.” A learner seeking a high school equivalency credential incorporated concepts from leadership training into his personal goals: “Go to the base, go to the bottom, and baby steps. When I started this class, you get this imagination thing going, but it’s a bigger picture, it’s baby steps … subtle things, but the change is slow. It’s not imaginary, it’s more realistic about what it is going to take to get there.”

Becoming leaders and helping their communities and program were important to learners. In one participating center, learners chose to create a book that detailed their personal journeys to the USA. They wrote the book to help educate the community on who they were and how they came to live there. “I strongly believe in time everyone will understand immigrants. It’s better for us to share our story. This book is really good for this community,” expressed one adult learner. The leadership project gave learners a sense of ownership in the program and helped them display leadership qualities they were developing.

Opportunity

A theme of opportunity is divided into two parts: opportunity for self and opportunity for others. By completing the program and learning new skills, learner leaders created new opportunities for themselves. “The project help me a lot to obtain the necessary skills to get my citizenship and to have a job in [county],” said one learner. Another learner added, “[in] my job I was low low low but once I started coming to school learning … I’m up there now, #1 sales associate for district.” Learner leaders worked hard to create ways to promote the program by using existing and new skills.

Many learners expressed such deep appreciation for how adult learning impacted their lives that they wanted others to embrace the same opportunities. One desired to “tell others about the program, how important it is and [how] much they can achieve.” Another added, “My contribution to the program is to pass the word to other[s] about this facility.”

Limitations

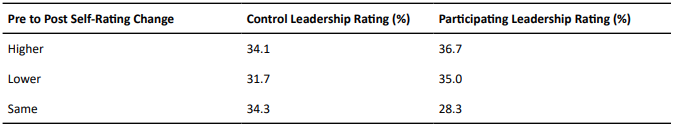

We note some limitations to the paper. First, while re-analyzing surveys after viewing videos, we noticed learners’ self-perceptions of leadership changed over time. In both experimental and control conditions, some learners’ leadership ratings decreased significantly. What we observed on video and in observation protocols does not mirror growth in self-rating— especially in programs receiving leadership training. Lack of selfconfidence, language barriers, or misunderstanding what “leadership” encompassed until participating in the project may have contributed to those results (see Table 2).

Also, except for two learner leaders in the movie, we were unable to interview individual learners to ascertain their feelings or reactions to leadership. We had to rely on written survey comments, which was sometimes difficult for English learners.

IMPLICATIONS

Our findings suggest multiple implications for adult educators wishing to cultivate adult learner voice through leadership. Implications include building relationships of mutual respect and validation and fostering collaboration and community to allow voice to thrive. Also important is engaging learners in relevant multimodal activities. In making recommendations, we seek to offer ways to enhance practice, support positive staff-learner interactions, and strengthen community in programs.

Building Relationships

First, building relationships of mutual respect can cultivate learner voice. Adult educators expect and deserve the respect of adult learners. Although we saw inspiring examples of mutual respect in staff-learner interactions, we were dismayed to see many staff-led interactions where staff did not return learner respect and treated learners like children or as if learners could offer little to learning. Adult educators must reflect critically on their personal perceptions of adult learners overall. Key is acknowledging that learners are first and foremost adults—many of whom have overcome huge hurdles to reach the program—with a right to respect.

One way staff can build mutual respect is to connect with adult learners as individuals. Building a stafflearner relationship starts with asking about the adult’s life story and experiences (Mezirow, 2007; NASEM, 2017). Relationship building can occur individually when adult learners first enter or during group orientation or goal setting, and it continues as adults share life experiences with peers while learning English or tackling fractions. In leadership settings, staff can model leadership by showing respect and guiding learners to respect peers.

Another way to develop voice is through staff validation of learner contributions (King, 2000; Schuller et al., 2002; Toso et al., 2009). When adult learners share or comment during instructional or leadership activities, staff needs to validate what learners say, communicate that their voice was heard, and build their confidence (Drayton & Prins, 2008). We noted instances in observations where a teacher would ask questions and repeatedly call on a single learner until other learners appeared to realize they would not be called on and disengaged. By engaging all adult learners, reaching out individually to hesitant learners by name, and affirming their contributions, adult educators support an environment of validation and respect.

To encourage positive interactions, adult learners need plenty of opportunity to develop and articulate questions (Schwarzer, 2009). Based on our research, learners need to answer those questions, too. While staff members are certainly resources and guides as learners gather more information, they can step back from a role of all-knowing “sage on the stage” (King, 1993) and instead validate learner questions, answers, and contributions.

Fostering Community and Collaboration

A second set of implications for cultivating learner voice involves community and collaboration. Adult educators can support voice by creating lessons that require collaboration, which in turn develops community. Block (2008) describes an environment that encourages collaboration: setting up tables for small groups, welcoming and connecting everyone, offering healthy snacks, and filling up walls with group ideas. As adult learners collaborate, community grows.

Next is involving adult learners in curriculum design or governance (Florez and Terrill, 2003; Schwarzer, 2009; Toso et al., 2009; Shiffman, 2018), which empowers programs toward leadership “of and by learners” (Toso et al., 2009). Leadership projects require adult learners to collaborate to design curriculum or complete program-supportive goals. Adult educators can encourage learners to share ideas, lead a lesson or meeting, or lead a project.

Encouraging Voice Through Activities

A final set of implications concerns engaging learners in relevant multimodal activities. First, activities need to be personalized and relevant to adult learners. In a participating program, for instance, adult learners with employment goals joined in impromptu mock interviews to hone employability skills. Learners practiced interviewing and gained highly relevant feedback from staff. The more adult educators can develop activities responding to specific goals that adult learners share initially, the more likely adult learners are to stay engaged. For example, if multiple English learners in a class state citizenship as a goal, activities can incorporate history, law, and government as context for learning English vocabulary. Additionally, adult educators can create opportunities for learners to share ideas on small group or tutoring topics; doing so assures learners their voices were heard.

Second, adult educators need to incorporate multiple modalities in teaching to enhance relevance. In observations and videos, we saw many examples of adult educators talking to adult learners without visuals, objects, or manipulatives. Adding photos, drawings, three-dimensional objects, manipulatives, and opportunities to write or draw offers adult learners multimodal activities. For example, one teacher in a video employed a post office handout in an English lesson. Along with written postal vocabulary, handouts showed a drawing of the post office counter, which learners could label and use to ask questions about mailing a package to family back home. Learners were actively and enthusiastically engaged in a paired activity that they could try independently later. Pictures from photo dictionaries or forms from websites could easily be incorporated into a similar lesson, so that learners see the place they are learning about and manipulate actual forms. Since many adults perceive themselves as hands-on or visual learners, learning through multiple modalities offers them additional ways to express themselves.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Much remains to investigate about connections of voice with adult learner leadership. Although we surveyed learners on what they gained during leadership projects, we did not interview adults to ascertain their reactions to leadership, and future researchers could consider doing so, preferably in the adult’s native language. Planning to interview adults in leadership roles at regular intervals across time would also benefit future studies, so that growth in learner voice can be measured at multiple time points as adults gain leadership skills.

Another recommendation for future researchers is to further investigate the role of humor and persistence. We were intrigued by examples of laughter in videos of staff-learner interactions. Researchers could consider how learner leaders employ humor in collaboration and communication and the extent to which learners who perceive the advantages of humor also complete a program or meet goals in their families, communities, or workplaces.

Turonne K. Hunt is a doctoral student in the field of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Virginia Tech. Currently, she is the director of Transitional Day Program. She holds a master’s degree in Educational Leadership and a bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education from Radford University.

Turonne K. Hunt is a doctoral student in the field of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Virginia Tech. Currently, she is the director of Transitional Day Program. She holds a master’s degree in Educational Leadership and a bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education from Radford University.

Amy Rasor is a doctoral student in the Department of Higher Education at Virginia Tech. After working in a research laboratory for 20 years, she now serves as an academic advisor to undergraduates in Virginia Tech’s Department of Biochemistry. She holds a master’s degree in Food Science and Technology and a bachelor’s degree in Chemistry and Economics from Virginia Tech.

Dr. Margaret Patterson, Ph.D., Senior Researcher with Research Allies for Lifelong Learning in the Washington, DC, metro area (www.researchallies.org), partners with non-profit organizations, postsecondary institutions, and state agencies to apply research and conduct evaluations which support adult educators and learners. She led the award-winning Adult Learner Leadership in Education Services (ALLIES) evaluation for VALUEUSA, the national organization of adult learners. Previously, she served as Research Director at GED Testing Service and Associate Director of Adult Education in Kansas. She administered and taught in adult education programs in Nebraska, Nevada, and Kansas and presents extensively throughout the USA.

REFERENCES

Block, P. (2008). Community: The structure of belonging. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Cherrstrom, C. A., Zarestky, J., & Deer, S. (2018). “This group is vital”: Adult peers in community for support and learning. Adult Learning, 29(2), 43-52.

Drayton, B., & Prins, E. (2008). Participant leadership in adult basic education: Negotiating academic progress, aspirations, and relationships. In M. L. Rowland (Ed.), Proceedings of the 27th Annual Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, Community, and Extension Education (pp. 50-55). Bowling Green: Western Kentucky University.

Florez, M. C., & Terrill, L. (2003). Working with literacy-level adult English language learners. Center for Adult English Language and Acquisition. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/caela/esl_resources/digests/litQA.html

Freiwirth, J., & Letona, M. E. (2006). System-wide governance for community empowerment. The Nonprofit Quarterly. 13(4), 24-27

Kennedy, D. (2019). A framework for asset-focused advocacy in adult ESL education. In H. A. Linville & J. Whiting (Eds.), Advocacy in English Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 133-146). New York, NY: Routledge.

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30-35.

King, K. P. (2000). The adult ESL experience: Facilitating perspective transformation in the classroom. Adult Basic Education, 10(2), 69-89.

Mellard, D., & Scanlon, D. (2006). Feasibility of explicit instruction in adult basic education: Instructor-learner interaction patterns. Adult Basic Education, 16(1), 21-37.

Merriam, S., B. (2009). Types of qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2007). Adult education and empowerment for individual and community development. In B. Connolly, T. Fleming, D. McCormack, & A. Ryan (Eds.), Radical Learning for Liberation (pp. 9-17). Dublin, Ireland: Maynooth Adult and Community Education

Mitra, D. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106(4), p. 651-688.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Health literacy considerations for outreach. In Facilitating Health Communication with Immigrant, Refugee, and Migrant Populations Through the Use of Health Literacy and Community Engagement Strategies: Proceedings of a Workshop (pp. 11-15). doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24845

Patterson, M. B.. (2016a). “A big and excellent opportunity for my future”: ALLIES evaluation. Media, PA: VALUEUSA. Retrieved from http://valueusa.org/projects

Patterson, M. B. (2016b). ALLIES final year leadership report: Part 2, qualitative summary. Media, PA: VALUEUSA. Retrieved from http://valueusa.org/projects

Patterson, M. B.. (2017). ALLIES: What VALUEUSA learned about learners as leaders. Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education, 6(3), 35-49.

Patterson, M. B., & Song, W. (2018). Critiquing adult participation in education report 1: Deterrents and solutions. Vienna, VA: Research Allies for Lifelong Learning. Retrieved from http://valueusa.org/projects

Ramirez-Esparza, N., Harris, K., Hellermann, J., Richard, C., Kuhl, P. K., and Reder, S. (2012). Socio-interactive practices and personality in adult learners of English with little formal education. Language Learning, 62(2), 541-570. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011. 00631.x

Schuller, T., Brassett-Grundy, A., Green, A., Hammond, C., & Preston, J. (2002). Learning, continuity and change in adult life. London, England: London University, Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED468442.pdf

Schwarzer, D. (2009). Best practices for teaching the whole adult ESL learner. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 121, 25-33. doi: 10.1002/ace

Shiffman, C. D. (2018). Supporting immigrant families and rural schools: The boundary-spanning possibilities of an adult ESL program. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(4) , 1-34. doi: 10.1177/0013161X18809344

Sperling, M., & Appleman, D. (2011). Voice in the context of literary studies. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(1), 70-84. doi: 10.1598/ RRQ.46.1.4

Stein, S. G. (1997). Equipped for the future: A reform agenda for adult literacy and lifelong learning. Washington, D.C.: National Institute for Literacy

Toso, B. W., Prins, E., Drayton, B., Gnanadass, E., & Gungor, R. (2009). Finding voice: Shared decision making and student leadership in a family literacy program. Adult Basic Education and Literacy Journal, 3(3), 151-160.

Tuckett, A. (2018). Adult education for a change: Advocacy, learning festivals, migration, and the pursuit of accessibility and social justice. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education. doi: 10.1177/1477971418796650

TABLE 1: CHARACTERISTICS OF THEMES CONNECTING VOICE AND LEADERSHIP

TABLE 2: CHANGE IN SELF-RATINGS FOR LEARNERS WHO COMPLETED BOTH YEAR 1 AND YEAR 2 ASSESSMENTS