Karla Walker

Southwest Adult Basic Education

Leading, to me, is about having a goal and working towards it. As a scientist, though, I know that many times we learn more from mistakes or unexpected results. Our division needed to develop new curriculum to help adults earn their High School Equivalency Diplomas (HSEDs). Our chosen expected goals were: 1) to shorten the time students took to complete the program, 2) develop transition to college or employment, 3) allow for poverty-informed decisions within the program, 4) develop cohorts, and 5) integrate the use of technology. The unexpected achievements we encountered were: 1) the effects of team teaching the curriculum, 2) the reduction of academic anxiety, 3) the acknowledgement of accomplishment, and the 4) importance and difficulty of developing time management skills. Here is our story.

WHY THIS COURSE THIS WAY?

We set our goals for this course in alignment with the College and Career Readiness Standards (CCRS) shifts of complexity, evidence, and knowledge for English Language Arts/Literacy and focus, coherence, and rigor for Math. The English Language Arts shifts in the Wisconsin Adult Basic Education state curriculum were to combine reading, writing, and communication instead of maintaining curriculum standards for each category. The shifts highlighted spiraling and integrating curriculum around themes. These themes were bound to the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). It challenged the state to combine resources and create partnerships, look to labor market data and industry research to determine which skills the workforce needs, and focus on the creation of a workforce that can meet the expectations of the future economy. Our dean and associate dean took all these initiatives into consideration, put forth their goals for a revision of this program, and provided time and space for its development. They then chose experienced teachers they respected who had worked at the state level on the revision of the state competencies aligned to CCRS. The main concepts of integration, themes, coherence, rigor, complexity, and workforce needs all came together into thematic integrated units that cover all the competencies of seven courses and promote pathways to work or college.

CHANGING THE PROGRAM

The revision was from a 30-year-old program that had students working on individual siloed curriculum at their own pace. Some students had been in the program for over 10 years.

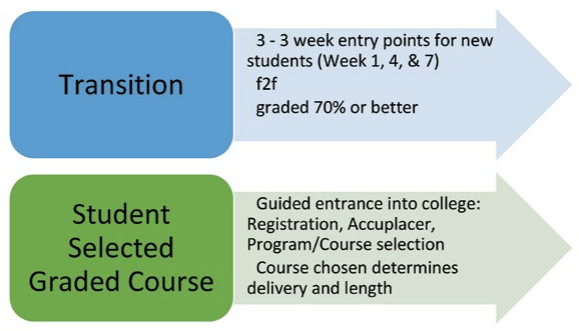

Although we were still very committed to shortening the time it took to get an HSED, after the first semester of implementation, we determined that requiring a second semester of instruction with an addition of individual pathway pursuit was necessary to achieve our second goal of transition to college. There just wasn’t enough time in one semester to accomplish all the material. The employability course was removed from the content course because the curriculum could be expanded to provide more depth on writing and computer skills while focusing on the individuals’ transition goals, which aligned better with the WIOA goals. In this course, called Transition, students write resumes and cover letters, build a personal webpage for branding, and maximize the employability skills they have. They also have an option to obtain Credits for Prior Learning (CPL). These credits are from their own work or life experience that translate into a course offered at Western Technical College.

During the second semester we also required each student take a graded course of their choice/ability, ideally in preparation for a program they are interested in entering. We do not have enough students to provide multiple-pathway instruction to our HSED students, but by compelling them to take a college course before high school graduation, we put students on an individual pathway by design. It also compels students to apply to go to college, fill out financial aid and scholarship forms, and participate in college/career counseling. Therefore, our HSED students transition into college students just by being in the program. By straddling the high school and college gap, students who may struggle with curriculum or college processes are supported by classmates and instructors that they have built relationships with among their cohort. This eases their transition if they decide to enter a program and allows them the opportunity to choose their path to a career.

An online version of the first-semester curriculum was built after three semesters of the course had been taught. It was initially designed for students in outreach locations or night classes at the request of the dean and associate dean. It has since become the third leg of our program. Students can take the whole first semester online, but they can also complete individual units if they have missed some from the face-to-face class. This works well for students who may have had life interrupt the two-semester program.

TEAM TEACHING THE INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

The team decided early on that, to achieve the goal of integrating the curriculum of the seven course areas of health, social studies, communication, math, science, and computer literacy into a semester, we would need a team of two experienced teachers in the classroom throughout the class time to ensure rigor, just-in-time learning, and expediency. One teacher would have expertise in math/science and the other would have expertise in reading/writing/communication. Although research shows that team teaching is good for students, it is expensive. Our leadership committed to team teaching because it also paralleled the division’s goal of reducing poverty and providing an education for the most at-risk adults in our community. The curriculum the teachers developed created as many lessons as possible that would have more than two courses reflected in their competencies. They also collaborated with expert resources throughout the college in social studies, online resource evaluations, and economics in the creation of the lessons. Links to careers and programs at the college are embedded whenever possible.

Most of the lessons/activities had to be created by the lead teachers. Some existing resources were used, like iCivics, but many of the materials are excerpts from articles (“You Can Grow Your Brain,” “Surrendering” by Ocean Vuong, and “Trends in Migration to the U.S.”), primary documents (the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence), or non-fiction books (Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand, Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly, and How Not to be Wrong by Jordan Ellenberg). We have also used Ted Talks, and parts of the videos Liberty, and America: The Story of US. One lesson includes reading the article “You Can Grow Your Brain.” It presents the research findings that by exercising your brain, you can learn throughout your life and that it is a myth that you can’t get better at math. This lesson not only provides an opportunity to learn about reading skills, comprehension, and reading strategies, but also math anxiety and scientific methods. In another lesson, we have students pretend they are on a desert island together (building cohort, problem-solving, and critical thinking). They must choose 10 items from a sinking ship that might be useful to them to survive. We then weigh (mass and weight) all the chosen items using pound and gram scales (math and science measurement skills). This sets them up to learn metric and English-to-metric conversion to get a total mass in kilograms. As a third lesson example, we read a prologue from the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot and talk about cancer and mitosis. We include the Ted Talks “We Can Start Winning the War Against Cancer” by Adam de la Zerda and “What You Need to Know About Crispr” by Ellen Jorgenson. The lesson includes instruction in reading strategies, vocabulary and word parts, and notation skills. We also color a picture of mitosis and label the stages of that process (science concepts).

The college dean and associate dean committed to trying these innovative and expensive practices to see what would happen. It isn’t that this curriculum couldn’t be taught by one teacher, but, as we mentioned before, we all underestimated the value of modeling professionalism and student skills to the students that team teaching provides. When one instructor was leading an activity, the other teacher acted like an excellent student: asking questions, excited about learning, taking notes, and modeling how to get the most out of an education. This alternated between the initial teachers. We didn’t announce each teacher as a model student, but if the teacher took notes, the students saw that and got busy. If the teacher asked questions, the students felt free to ask theirs. We also modeled healthy professional interpersonal interactions without having a lesson on it. It included; respect, courtesy, problem-solving skills, how to ask questions, working with others, struggling with the material, and pride of accomplishment. Team teaching has become central to our program because of its unexpected positive benefits. It is worth mentioning that the team-teaching approach is also helpful with regard to the specific needs of the adults we serve. If there are student issues that arise, class can continue, and one teacher can address the needs of the individual student right away without disruption to the other classmates.

COURSE STRUCTURE

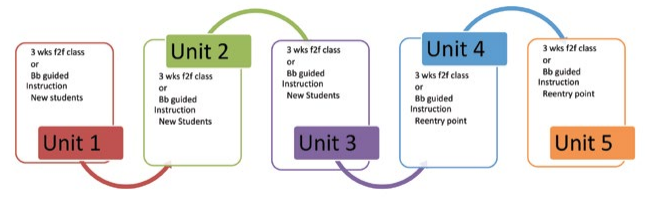

During the development of procedures for the program, we were aware that we needed to help develop time management skills in the program. The dean and associate dean recognized that the students targeted for a high school equivalency degree are likely to have many outside influences like generational poverty, incarceration issues, familial responsibilities, and addiction issues. The solution the leadership team devised was to develop five units of three weeks each for our 15-week semester. Each unit has a theme and a guiding question. The themes are preparation, building, balance, challenges and obstacles, and change. The themes reflect the students’ process of getting a diploma or starting a career. At first, they need to get prepared, then they are building their skill. Along the way, they need to balance many things and there will be challenges and obstacles. Finally, there is change, leading to graduation. The guiding questions for each unit are social studies/ civics based. They are:

These questions provide a theme for the unit. The lessons within the units are designed with these questions in mind. The instruction allows for exploration, problem-solving, and reflection. Students need to complete all five units, but they don’t necessarily need to take them in sequential order. Students may step out of the face-to-face course due to personal circumstances and then choose to complete the missed unit using the online version. The online version is more individual and doesn’t build the cohort and develop as many transition skills, but it does provide an opportunity for students to learn the same competencies found in the face-to-face curriculum, and it is a safety net for students who may need this option. (See Appendices A and B.)

DEVELOPING TIME MANAGEMENT SKILLS

We often tell our students (and past students tell future students) that the hardest part of this course is getting here. Time management is a great transition skill for our students. It sets a foundation for being a good college student or employee. We don’t have formative assessments during the semester, but we have an attendance policy and include participation in the class as attendance. In other words, if a student is sleeping for an hour, he or she is considered absent. If students miss over six hours of class time, they meet with the teachers and a counselor to make a different plan or problem-solve solutions, which may include returning later or opting for the online version. They are not considered out of the program, just on a different plan. (See Appendix C.)

Many of the policies and procedures within the program are there to serve an at-risk population. The three-week units that provide an opportunity to enter or exit at multiple points, the support of two teachers, the support of a counselor, the focus on a future, the cohort building, and the anxiety-reducing environment all contribute to the success of nontraditional students. There have been many instances where students have benefited from this design: the student who was being beaten at home and needed to step in and out over two years, the student who needed an abortion, the student who had no babysitter and needed time to find one, the student who was struggling with addiction and stepped in and out over a two-year period, the student who lost his mother to a heart attack, the student who was incarcerated periodically. It is our belief that once students start the program, they are in it until they complete. This program provides the flexibility and options needed, while maintaining the rigor and high expectations these students can achieve.

REDUCING ACADEMIC ANXIETY

This curriculum design is a non-testing route for students to obtain their HSED. To combat the test anxiety most students arrive with, we don’t do formal assessments. We do multiple informal assessments and talk about their future from day one. Both practices are spiraled within the curriculum throughout both semesters. Using a variety of delivery methods that boost confidence and multiple opportunities to work with everyone in the class, students develop cohort relationships that reduce their anxiety through the second semester as they take one course with the cohort (transition) and one on their own, depending on their graded course choice, in math, writing, or science. The themes of the five units in the first semester provide an opportunity to talk about how the students are progressing toward their future. The written and online documents and products they produce in the second semester are all about a future they design themselves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF ACCOMPLISHMENT

When we started teaching the course and got to the end of the first unit, we had a leadership team discussion concerning how to celebrate or acknowledge this accomplishment. We weighed the options between doing nothing and providing students with a certificate. We were concerned about giving out a certificate for each unit when we really wanted them to complete all five. We also felt that getting through one unit was a big deal for us as instructors, so we thought it might feel that way for the students, too. We decided on certificates and it was a very humbling experience. It continues to be. Students were overcome with emotion and reported that they framed their certificates or put them on their refrigerator. We hand the certificates out at the end of each of the three-week units and shake hands and clap for each student as practice for when they walk across the stage in a black gown. The certificates are a meaningful recognition of students changing their lives and accomplishing something. It is good leadership that allows for experimentation and acknowledgment of success.

SUMMARY

We accomplished our goals. We did it together. We shortened the time it takes for students to obtain their HSED. We provided a transition to college or career for these HSED students. We have a program with the flexibility needed for adult students to earn their HSEDs. We have developed cohorts that support students working toward achieving their goal of earning their HSEDs. We have integrated the use of technology in a meaningful way so students can get future jobs with their HSEDs. We have created a learning environment that reduces anxiety and provides just-in-time learning with rigor and high expectations so that our students feel pride in themselves when they earn their HSEDs. We have taught them how to manage their time and prioritize learning and their future. We have developed a program, not just a course.

This is our favorite class to teach. We think it’s because what we learned from teaching an integrated spiraled thematic high school equivalency class is just as important as what the students learned. Few teachers and administrators get the chance to take the lead in creating an innovative curriculum that can be team taught with the budgets of today. The team-teaching benefits, the reduction of anxiety, the pride we feel and see in our students, and the maintenance of high rigor in curriculum and time management were a sweet surprise to us. We watch adults grow before our very eyes. They seem to walk taller, smile more, engage in discussions and conversation at a college level, and dream of a different future for themselves and their children.

Karla Walker has been in public education for 25 years. She has taught high school biology, life sciences, chemistry, and physical chemistry in Wisconsin and Texas. She has taught pre-algebra, basic math, biology, and chemistry at the technical college level in Wisconsin.

Karla Walker has been in public education for 25 years. She has taught high school biology, life sciences, chemistry, and physical chemistry in Wisconsin and Texas. She has taught pre-algebra, basic math, biology, and chemistry at the technical college level in Wisconsin.

APPENDIX A: ADULT DIPLOMA PROGRAM

APPENDIX B: ADULT DIPLOMA (HSED 5.09)

Semester 1

Semester 2

APPENDIX C: ATTENDANCE POLICY

There are a few reasons why we landed on 6 hours of grace for attendance. One is that we are covering 6 different subject areas and theoretically students would be missing much larger portions of the curriculum on every subject area with more absence than 6 hours. We are grant-funded and must account for students’ hours of instruction, and there needs to be a reasonable amount of time in each subject area even though the curriculum is not siloed. A second reason for the attendance policy is that we are constantly building cohort and if there isn’t consistent attendance this process is stymied. In order to cover the topics and discussions in the later units we need to build trust between the students. A third reason for the attendance policy is that there are assessments being made on a daily/hourly basis. If students aren’t attending, they are getting a checkerboard instruction with lots of missing pieces. This is possibly how many of these students attended in the past, and it still doesn’t work. We are hoping to change attendance patterns so they can become better students or employees by building better attendance habits.

Finally, students are told that we are assessing their progress constantly and since we don’t have grades, tests, or homework assignments, the only thing we do insist upon is participation and attendance. Students rise to this standard. We have written determination on the board for a whole semester as a description of what it takes to succeed in this course/program. We have seen students problem-solve with us or with classmates about how to get to class on time. We do keep track of minutes since we have three-hour class periods. There is leeway on the first 15 minutes, but if a student has a habit of coming in late every day by the same amount of time, we talk about it. If you set the standard and provide quality instruction and a positive, safe environment, the students want to be there. When some students miss over 6 hours, they are upset and want to talk about being “kicked out.” As a team, we work hard to change the conversation to stepping out or doing what’s best for the student at the time. They are not “kicked out” of the program. There are just alternative methods of gaining the same knowledge if circumstances in their life are preventing their attendance, while upholding the standards set for the program